A Blog Based-On Mosquito Science By: Amy Anguiano, Biologist

WELCOME!!

We are excited that you stopped by!

The goal of this blog is to educate you on all things mosquito science. Beginning June 2025, our Biologist, Amy Anguiano will be sharing her knowledge and love of entomology with you and please, feel free to take what you have learned, and share it with family and friends.

Blog Entry 5

April 8, 2025

Blog Entry 4

February 12, 2025

Happy Valentine's Day

Blog Entry 3

October 31, 2024

Happy Halloween!

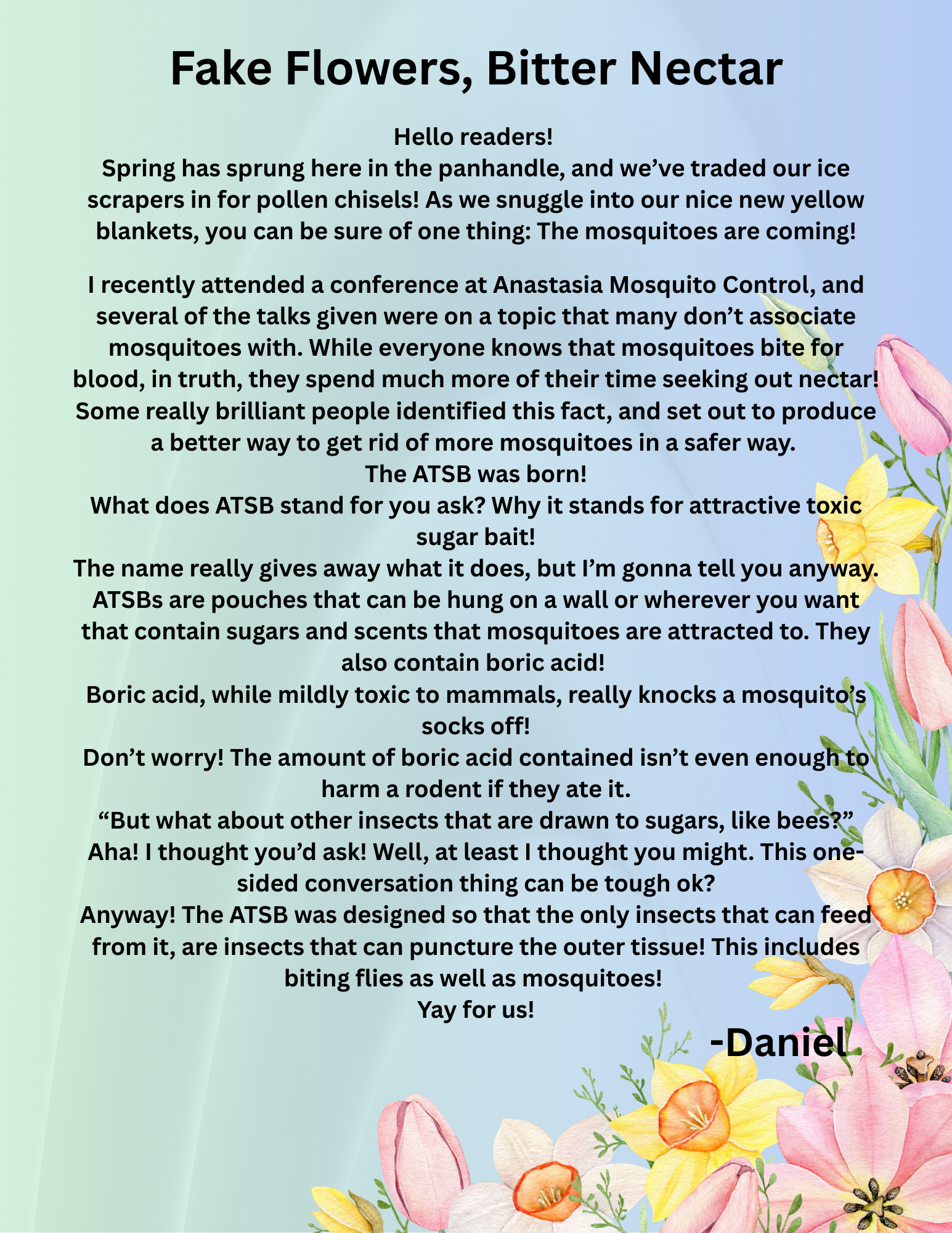

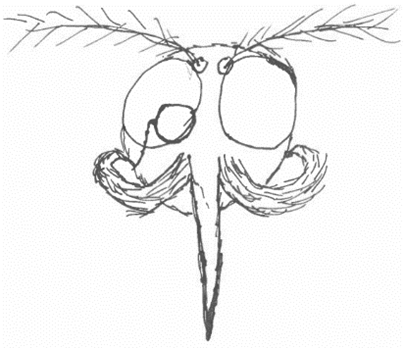

In this spooky edition of The Entomologist’s Corner, I thought we’d discuss the functionality of a mosquito’s proboscis. At first glance, the proboscis appears to be a simple needle, meant to puncture and draw blood. But there’s so much more to it! And if you ask me, it’s downright creepy! In this illustration by Robert Matheson (1944), you can see all the different parts of a mosquito’s proboscis. Using this image, let’s briefly discuss each part in order of use when biting.

The labium is a sort of soft sheath that keeps the other parts of the proboscis contained, nice and tidy when not in use. This part never actually punctures the host’s skin, in fact, it flexes backwards, out of the way as you can see in this image from cdc.gov.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=1533079c62d0d844fe0a933de569d995)

The labella are two sensory lobes located at the tip of the labium that serve as blood vessel detectors. That’s right! Mosquitos don’t just land and bite right away, they feel around for an ideal feeding spot first. Like scoping out the house with the king size candy bars!

Next up are the maxilla. Do you see how in the image above they look serrated? They are! It gives me the willies just thinking about it, but mosquitoes don’t just pierce the flesh. The two maxilla actually work together with the mandibles to SAW a small hole in the flesh while pressing forward. Yech!

The hypopharynx is a tiny tube-like structure that delivers the mosquito’s saliva into the host’s skin. This saliva prevents blood clotting, and provides a numbing solution so the host doesn’t start swatting too soon. Sounds awfully gross, huh? Well, this saliva is also capable of transmitting disease if the mosquito is infected. Bobbing for apples? No thank you!

Our final contender in the piercing proboscis party is the labrum. This is the actual blood sucker of the bunch! It’s very sharply pointed at the tip to help with the puncturing process, and it has a channel straight up the center to pull the blood through.

All those tiny parts exist and work flawlessly inside the proboscis of every biting mosquito, which is pretty creepy! But here’s a bonus tidbit! To further ensure a stealthy escape, mosquitoes use a combination of super-fast wingbeats (600 per second) and gradual leg extensions to lift off without a trace. Even Dracula can’t pull that off!

Be careful tonight, and watch out for ghosties!

-Daniel DeBord

Blog Entry 2

September 5, 2024

The Fabulous Facial Fuzz of Male Mosquitoes

September 7th is global Beard Day, and we at South Walton Mosquito Control District thought this was a grand opportunity to turn the spotlight toward the fuzzy faces of male mosquitoes! Perhaps you were unaware that male and female mosquitoes are different from one another? It’s true, and quite easily discerned! Behold the mighty facial fuzz of the male Aedes taeniorhynchus (left) as compared to his female counterpart.

He may not have a beard, but the male mosquito has quite a bristly brow. And get this, it’s not just for looks! The hairs, or setae in entomologist-speak, are actually capable of detecting sounds and smells!

Sir Squeebington:

“Ears? Nose? BAH! All I need is my fabulous mustache!”

The lower brushy branches extending from our friend’s face are called “palps” and are mostly used for detecting food and other smells. The upper branches are the male mosquito’s antennae. The setae located here are extremely sensitive to vibrations in the air, and the male mosquito uses them to detect the wingbeats of other mosquitoes. He can even decipher female wingbeats of his own species from others, which is how male mosquitoes find a mate!

Modern science is currently working on replicating this feat using infrared light sensors for automated in-field mosquito identification. Technology sure is cool!

Thanks for reading!

-Daniel D.

Blog Entry 1

August 7, 2024

DRY SUMMER- ANGRY MOSQUITOES

Have you ever wondered why, even during a dry Summer, the smallest rain shower can bring swarms of aggressively biting mosquitoes mere DAYS later? It’s all thanks to the incredible, not-so-edible, mosquito egg.

While there are a wide variety of different mosquito species out there, they can be bunched together in groups called “genus”. Within these groups, related species share common traits such as preferred habitats, biting times, and egg laying methods. If you’re running into aggressively biting mosquitoes in the daytime, days after a rain event, you’re most likely dealing with two main genus groups: Aedes, and Psorophora. But what do mosquito eggs have to do with anything? Why, everything dear reader, everything.

Aedes and Psorophora mosquitoes lay their eggs on dry surfaces with the anticipation of flooding events. Some species, such as Aedes albopictus, lay their eggs on the side walls of manmade containers or tree holes. But most other species of both Aedes and Psorophora lay their eggs on grassy areas, leafy debris, or even dirt with high humidity, indicating that this is a region that can flood easily. This is how these species always operate, so what difference does it make if the Summer is dry? Stress!

You see, mosquito eggs really are incredible in the fact that they can stay dry and not hatch for YEARS. However, these eggs have a sort of “stress threshold” built in. Under normal circumstances, mosquito eggs hatch at a gradual pace, progressing through 4 larval stages and a pupal stage before emerging as adults. BUT when exposed to drier environments for extended periods of time, they start to degrade, and less eggs remain viable. When these stressed eggs are finally exposed to water, the larvae burst out very quickly, and grow much faster than normal. It’s as though the larvae know that, given the previously dry conditions, this water isn’t likely to last long. The result of this phenomenon is a sudden, and often unexpected, wave of blood-thirsty mosquitoes. But take heart reader! The vast majority of these particular species are not carriers of mosquito-borne illness.

Your local Mosquito Entomologist,

-Daniel